Systems Thinking: Ackoff excerpts

By: Mauricio RIVERA — Posted 2021 Jan 06 under ARTICLES

We recently came across a transcript an interview of Dr. Russell ACKOFF and Dr. W. Edwards DEMING — two giants in American Management Science. Here are two gems from that interview.

Assigned Tags: Headline / Operations-Management / Systems-Thinking /

In this first of a series of articles on Systems Thinking, we will discuss excerpts from a ACKOFF-DEMING interview conducted back in 1992. Although almost thirty years have passed, the topics discussed then are still very relevant today.

But before we proceed, let's quickly go over the backgrounds of these two trailblazers in the field of Management Science.

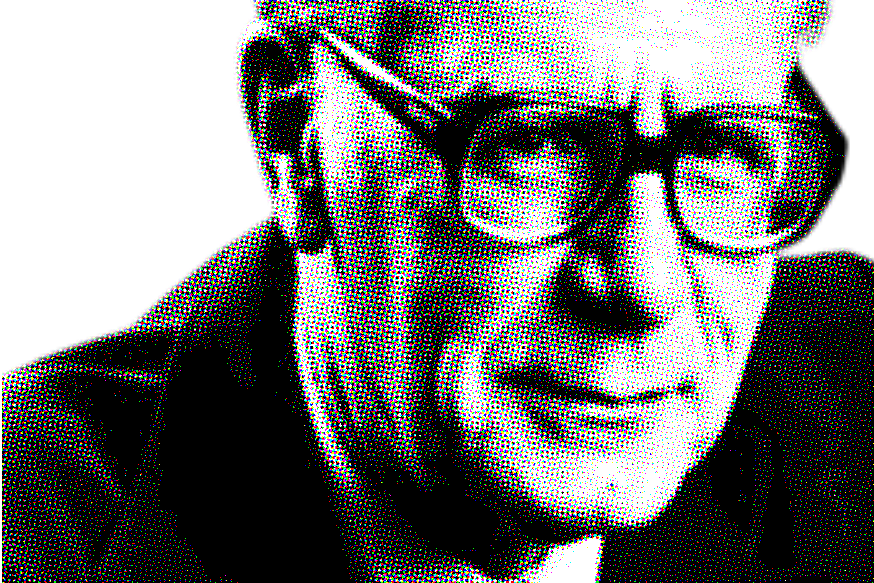

Dr. Russell ACKOFF was one of the pioneers in the field of Operations Research (OR), a discipline which aims to define optimal solutions to real-world problems. He co-authored (back in 1957), the field defining book “Introduction to Operations Research” — with Dr. C. West CHURCHMAN, another notable OR pioneer. He and Dr. CHURCHMAN were also two of the most influential proponents of Systems Thinking.

Dr. W. Edwards DEMING also had an outsized influence on the field of Management Science. Resulting from his work with Dr. Walter SHEWHART, he eventually championed Dr. SHEWHART's statistical control theories, and collaborated with him for several years. Dr. DEMING is known for his involvement in the introduction and spread of statistical process control techniques in post-war Japan. His effect on the eventual recovery of Japan in the years after 1950 cannot be underestimated.

Dr. Russell ACKOFF

Dr. W. Edwards DEMING

I became familiar with Dr. ACKOFF's work only through his documented interactions with Dr. DEMING, who was a popular figure in the fields of Total Quality Management and Statistical Process Control.

The interview between Dr. ACKOFF and Dr. DEMING shows the unique connection between these two legends. Having worked together in the US Bureau of Census back in 1950, the two had similar and complementing views on management science — and since both were long-term educators, both shared common views as well regarding the state of education at that time.

We will discussing many excerpts from this interview, over a series of articles on Systems Thinking. Here are the first two excerpts from that interview.

Interview Excerpts 1 and 2

— ACKOFF: “Each part of the system can affect the behavior of the whole, but no part has an independent effect on the whole.”

— ACKOFF: “Therefore, the performance of the whole is NEVER the sum of the performance of the parts taken separately, but rather is the product of their interactions.”

EXCERPT 1: Each part of the system can affect the behavior of the whole, but no part has an independent effect on the whole.

To illustrate the concept that parts “can affect the behavior of the whole, but that no part has an independent effect on the whole”, Dr. ACKOFF would usually talk about the relationship of automobile parts vis-a-vis the automobile (the whole).

Parts can affect the whole, simply by not functioning properly. Let's look at a “car engine”, a PART of a WHOLE (system) called a “car”. If the car engine does not function properly, it affects the ability of the car to transport people.

However, the car engine does not — by itself — have an independent effect on the car; as its final effect on car performance would depend on its interactions with the other parts / subsystems of the car (e.g the transmission, suspension, electricals, body aerodynamics, etc).

So, for example, a car engine (the “part” in this example, which is actually a subsystem) would not have an independent effect on a car (the whole), as it needs to interact with other car systems (e.g. the fuel, electrical and transmission subsystems, to name a few) in order to perform properly (i.e. move the car).

If a car's engine does not function properly, it will definitely affect the car's ability to transport people or objects.

However, the car's engine functioning properly — in and by itself — does not guarantee the car's ability to transport people or objects, as this will depend on the engine's interactions with other systems (including the “car driver”).

Insight: Hence the need to look at the way parts interact with the whole, and also, with each other.

The engine, on its own, will not be able to move the car — unless it is interacting with the other parts (or subsystems) of the car. The car's movement will also be affected by other systems (e.g. the driver, weather, traffic, just to mention a few).

So why is this interesting? Current management methods mostly aim to control outcomes by focusing on causes and effects of "parts of an organization", but do not actively emphasize the importance of managing interactions between the parts in the organization's system.

A simple example of this would be ON-TIME-DELIVERY compliance failures.

At times, delivery date commitments are made to customers without proper consultations to the Production / Servicing / Warehouse / Logistics / Purchasing departments ... resulting in delayed deliveries due to promising what actually cannot be delivered.

In this case, the inability of the Production Lines to produce goods quickly enough to meet agreed delivery dates — wherein the delivery dates promised by the SALES function were not based on feedback or inputs from the PRODUCTION, MAINTENANCE or SUPPLY CHAIN functions — would be correctly classified as a systems issue.

In this scenario, the parts of the organization did not interact properly to serve the needs of the client / customer.

EXCERPT 2: Therefore, the performance of the whole is NEVER the sum of the performance of the parts taken separately, but rather is the product of their interactions.

Here, Dr. ACKOFF is trying to point out here that changes to the parts do not necessarily produce a proportional change in the whole, due to the nature of the interaction of parts.

A poorly running production line machine may not significantly affect the output of a process, due to interactions from the persons managing the process.

In the same way, replacing the poorly running machine with a high precision automated system does not guarantee a proportional improvement in the process output, again due to the nature of interactions.

Insight: Process Improvement activities need to consider ALL inputs into the process, whether it is material or otherwise — as well as ALL the interactions between these inputs AND other processes within and outside the organization.

Thus, to affect the whole (in this case a production process), improvements need to be made on their interactions between its parts (e.g. interactions between Production and Sales).

Using the scenario stated in EXCERPT 1 above as an example, one simple interaction-based improvement would be to have Sales and Production coordinate regarding expected production output — before finalizing commitments to clients.

This, of course, assumes that PRODUCTION already has had prior interactions with SUPPLY CHAIN and MAINTENANCE regarding the critical raw materials, in-process stocks and machine availability.

So what now?

If you find the statements above interesting — then it might be worth exploring the concepts behind Systems Thinking, and seeing how it may apply to your current situation.

We will also be going over more excerpts from the interview in the coming days, so keep an eye out for the next entries on our SYSTEMS THINKING series.

You can download the transcript from the ACKOFF CENTER WEBLOG site as a PDF, for your personal enjoyment.

Related links on SYSTEMS THINKING

Systems Thinking: How to Manage — Two more excerpts from the amazing 1992 ACKOFF-DEMING interview — now focusing on a SYSTEMIC APPROACH to MANAGEMENT.